Child Labour: Transnational Corporations and their Role in Safeguarding the Right to Education

Pre-existing wealth gaps are exacerbated, and post-Covid-19 consequences are, therefore, likely to include an increase of child labour, child marriages and other forms of child exploitation in addition to lost education[1].

Who should bear these losses and carry the responsibility to build back better, more just societies in a post-COVID-19 world?

Many low-income countries find themselves dependent on inward investment by TNCs to sustain their economies, create jobs and sustain livelihoods of their citizens. This however, puts them in a vulnerable position and allows for exploitation.

TNCs possess a large amount of the world’s wealth, and control approximately $18 trillion of global wealth; in comparison, there are 2 billion workers that comprise the informal economy, who work below the Average Minimum Wage[2]. Estimates suggest that in the first month of the crisis there was a 60% drop to the income of the 2 billion global informal workers[3]. A staggering amount of this capital has been accumulated through their use of “cheap child labour”, often at the expense of their safety and well-being, including their rightful access to education.

TNCs, should rise to the challenge of supporting and safeguarding the right to education for children in those countries where they operate.

Yet very little is re-invested into the countries where TNCs utilise cheap labour. The approximate wages offered by TNCs are often less than $1.90 per day[4] which, is defined by the World Bank as beneath extreme poverty[5]. Rather than stimulating growth, development and empowering communities, they gain a significant advantage by using children, often in harsh and dangerous working conditions. Although TNCs employ Corporate Social Responsibility measures, this is not enough. They must work to ensure and support the Countries they operate within, have measures that adhere to international legal standards with a particular emphasis on ensuring children attend schools and are not members of the workforce.

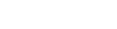

The developing world as a source of cheap labour creates a vicious, regressive cycle, in which children must work in order to supplement the household’s income, causing children to become vulnerable to exploitation. This exploitation usually results in the loss of the children’s’ education, and entraps children from a young age into poverty.

School closures and interrupted learning combined with the economic impact of a drop in global economic activity, will likely exacerbate the use of child labour forcing children to support their household’s finances. The expected increase in child labour will hinder current and future generations, as it has been shown that ‘children who enter child labour – are unlikely to stop working even if their economic situation improves’[6].

So what can be done? A good start would be to recognise that TNCs are actors in their own right who owe duties to communities and children who are within their economic and social influence. This can then, be the fundamental principle for international law conventions, charters and treaties, as well as in the application of existing legal norms. TNCs should also be subject to the jurisdiction to the Rome Statute[7] so that they could be held accountable in the International Criminal Court. International law and regulation is not, however, a substitute for national remedies and action. Accountability at a national level is crucial because national courts and judges are closer to the social problem, and they are in a unique position to understand and protect their own citizens. There is a glimmer of hope, because some national courts, such as the UK courts and US common law, are moving towards a more progressive approach, perhaps because of the increasing power of environmental movements and advocacy campaigns that create calls to action that hold TNCs accountable., It is also important to make clear the relationship between powerful TNCs, child labour and the right to education, such as in the open consultation for the 2021 GEM report, that is focusing on the role of NSAs (Non-State Actors) in the context of education. TNCs are part of the problem but they could also be part of the solution: the negative aspect (regulating TNC exploitation of children) and the positive vision (TNCs investing to safeguard quality education for children) needs to be discussed, analysed and debated more openly.

The top down approach through legal regulation, supported by grassroots mobilisation can be combined to advocate for accountability of TNCs that exploit child labour. Today, on World Day Against Child Labour we must call for an open discussion about the negative and positive role of TNCs in safeguarding quality education for the world’s most exploited children.

[1] David Jaume and Alexander Willén, ‘The Long-Run Effects of Teacher Strikes: Evidence from Argentina,’ Journal of Labour Economics 37, no. 4 (October 2019): 1097-1139

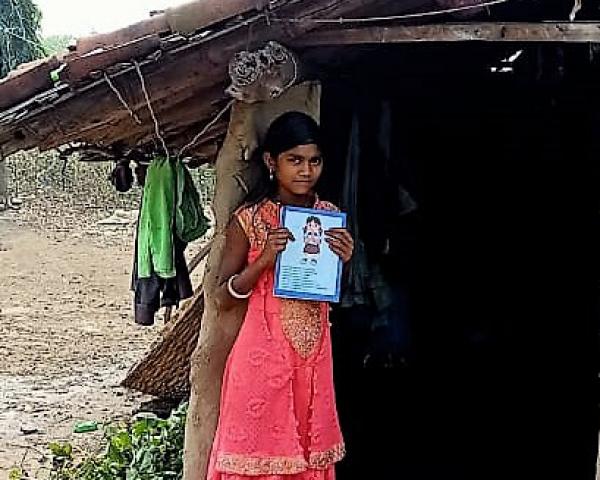

About the author

Abdulaziz Al Thani is a Law and Policy Officer at Education Above All Foundation (EAA), specialising in the protection of the right to education in conflict and insecurity. He is a law graduate of Kingston University, UK where his academic studies included a focus on international law and policy. At EAA, Abdulaziz has developed a specialist interest in policy research, which included work as part of the team that researched and produced the BIICL-EAA 'Protecting Education in Insecurity and Armed Conflict: An International Law Handbook', 2nd edn, (2019). He worked on the EAA-ICRC project on Education As a Humanitarian Need that led to the publication of EAA-ICRC 'The Role of Humanitarian Actors in Safeguarding Access to Education'.

[2]‘More than 60 percent of the world’s employed population are in the informal economy’ (ILO, 2018) <https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_627189/lang--en/index.html>

[3] ‘ILO: As job losses escalate, nearly half of global workforce at risk of losing livelihoods’ (ILO, 29 May 2020) <https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_743036/lang--en/index.htm>

[4] Annie Kelly, ‘Apple and Google named in US lawsuit over Congolese child cobalt mining deaths’ The Guardian (London, 16 December 2019)

[5] ‘Poverty’ (World Bank, 2019) <https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview> accessed January 12 2020; Although, the figure supplied by the World Bank has come under criticism, and other actors argue that $7.40 is a more accurate figure to account basic nutrition and human life expectancy

[6] ‘Why child labour cannot be forgotten during Covid-19’ (Unicef, 14 May 2020) <https://blogs.unicef.org/evidence-for-action/why-child-labour-cannot-be-forgotten-during-covid-19/>

[7] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (2002)